My Father

My mom and dad, then Elsa Stern and Sali Levi, 1930

My mother is at the heart of my upcoming book, In the Wake of Madness, but my father was the brains behind their escape from the Nazis. Luck, of course, played a considerable role, but my dad’s astute watch over the world stage and his business savvy helped make it possible. In these complicated times, I miss his nuanced, international perspective and our lively political discussions. It hardly seems possible that he has been gone from this earth for 40 years now and would have turned 120 this week. While his father, my Opa, was disappointed that my mother had given birth to a “mädchen” back in 1949, my Dad was perfectly happy that I was a girl, and, despite the social mores of the time, he never set parameters around my aspirations.

My dad spent long hours building a metal smelting factory in his adopted country, and he built a comfortable life for us in Queens – although, he confessed, he would have rather been a lawyer or doctor had the world been different. When he returned from work, he would often stretch out on our velvety pea green living room sofa to read the New York World Telegram, his legs resting across my lap. Soon he would be snoozing. I never moved for fear of waking him, but I never minded being trapped; we were connected. After Opa died, we went to “shul” every Shabbat for eleven months so that my father could recite the Mourner’s Kaddish. I absorbed what I could from the sermons of our socially progressive rabbi, but a handful of carefree Sundays are my sweetest memories. My mom and brother would sleep in, leaving us to our own devices until noon. Dad whisked me off in his Buick Electra into neighborhoods unknown to us. “Let’s get lost,” I pleaded, and he obliged. I was thrilled by new spaces, and tickled to share these secret adventures. Once we visited the modern pavilions of TWA and Pan Am at Idlewild Airport, watching the Boeing 707s take flight to faraway places. On another outing, we stopped at King George, a hamburger joint in Forest Hills that delivered your order, if memory serves, via a model train routed around the counters. The details are likely inaccurate, but the feeling was pure magic.

Clockwise from top left: with sister, Bettina; looking all grown up before he was; at the beach with his best friend and future brother-in-law, Gerhard; passport photos of my parents one month before they left Lisbon for New York.

Robert, the name my father adopted when he came to America, never lost his European formality. Typical dress was a pressed white shirt with cufflinks, a somber suit, Florsheim wingtips, and a homburg hat. His hair was slicked down with Eau de Pinaud, a Portuguese hair tonic, and an unlit cigarette dangled from his mouth. His outfit reflected his demeanor: he was a serious man – which is why it was so wonderful to see him relax or laugh. Seeing photos of his younger days, you can already see his sense of purpose. My mother was a light spirit by comparison, and that optimism may have buoyed him more than he realized. When she persuaded him to wear casual shirts or branch out into pale blue, it was a banner day.

My father was 46 years old when I was born, but I never realized my parents were older than those of my peers. In fact, I first learned his age when I applied for a college scholarship, and that information was required. It was just one of the many things – both significant and trivial – that my parents didn’t talk about.

In my adolescent years and early twenties, we had lots of conflicts as my boundary-testing collided with his “what will people think” rigidity. But we always made it through because we loved each other. As I was writing In the Wake of Madness, I often felt his absence. I regret deeply that I did not make more time to ask more questions about his past, but I am grateful he was present for me when it counted.

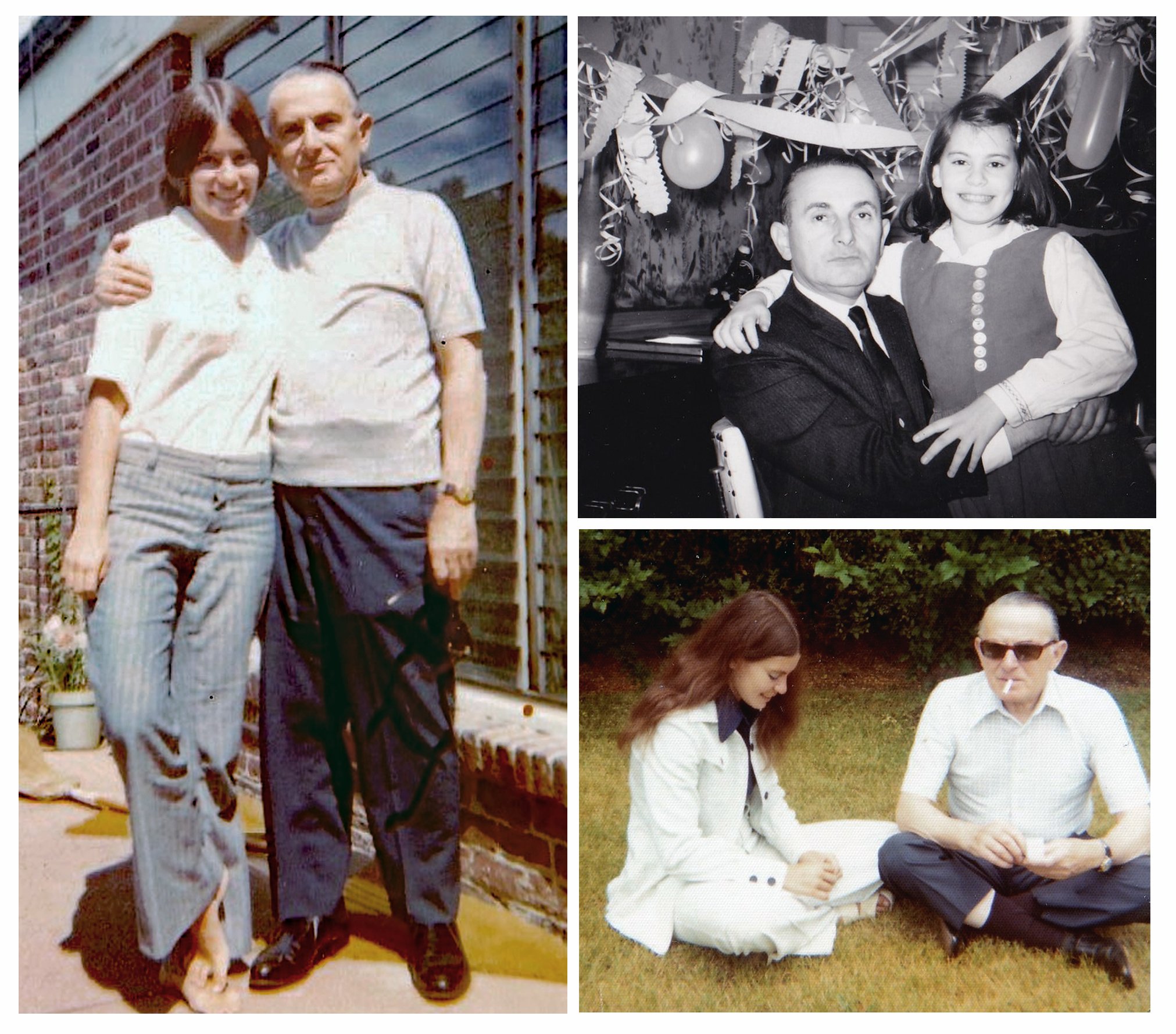

From left: At our second home in Long Beach, New York, in the day of bell bottoms; a New Year’s Eve Party at our home, 1959; a leisurely visit home in my 1970s leisure suit.

I had hoped to write this tribute without thoughts of antisemitism, but in the last few days, the specter of hatred against Jews – and “others” in general – has again stolen the conversation. I don’t honestly know what my father would think. Having fled the Nazis and then seen the rise of McCarthyism, he might look over his shoulder as he once did, speak more quietly in his own home, take off his yarmulke before walking home from shul. I know only that he would have been tired of such senseless tragedy – but not too tired to worry.