Pithole, USA

There's a fascinating sidebar to this story that I placed at the very end. Don't miss it!

Simeon Small was a man who intuitively appreciated the natural world. In Burying My Dead, his photographer’s eye saw beauty everywhere: in a changing sky, geese flying overhead, the colors of autumn. Letters from his friend, Tracker, persuaded him to set out on the Oregon Trail, but photos of the Columbia River Gorge cemented his resolve.

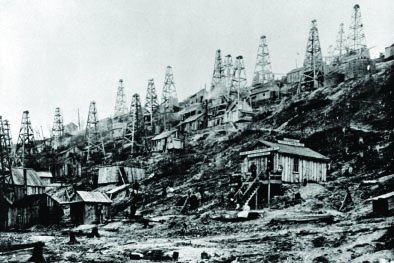

The rough and tumble oil town of Pithole

Vista Point along the Columbia River Gorge

Oregon’s untainted landscape stood in stark contrast with Pithole, Pennsylvania, where Simeon spent a disappointing day in search of fortune. “The once verdant landscape…was dotted with stumps; gone were the stately white pine and rock maple that graced the slopes, giving shelter to deer and squirrels and birds. In their stead stood oil derricks strewn like skeletons on a battlefield of greed.”

In my historical novel, Burying My Dead, Simeon Small, visits Pithole briefly in search of his fortune. I imagined that he saw steep hills riddled with derricks instead of trees, as seen in this photo of the Pioneer well along Oil Creek.

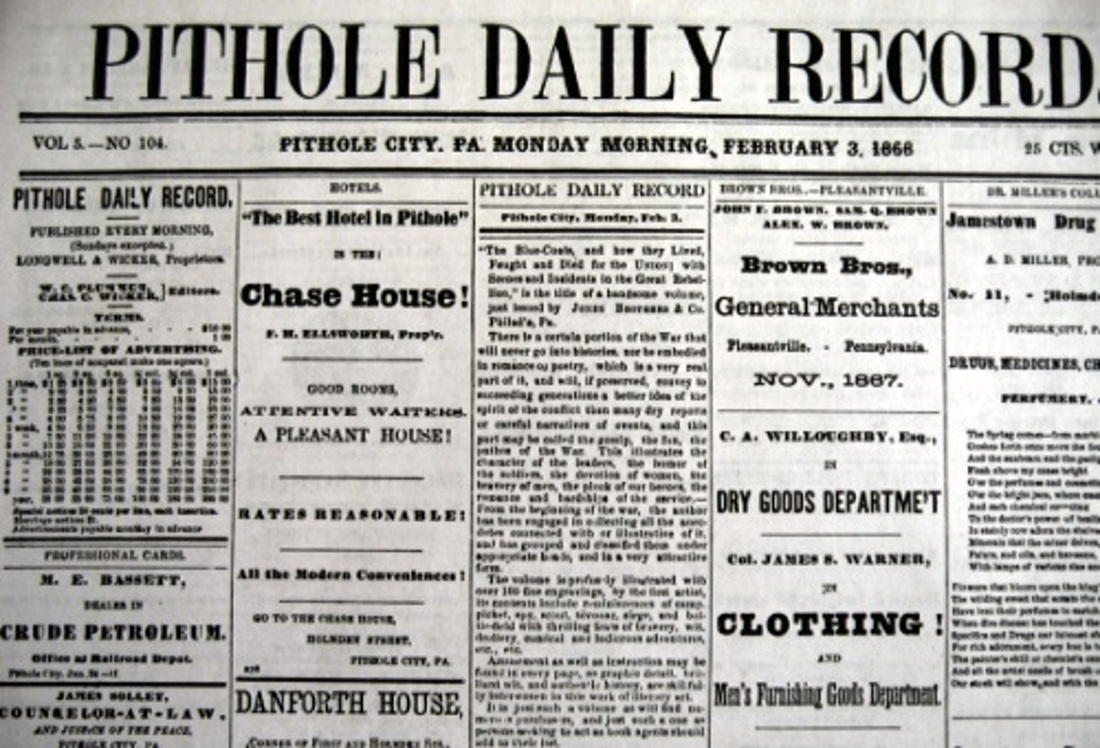

While researching Pittsburgh, I stumbled on this boom and bust town in the state, I was reminded, that once symbolized oil production. (Note Pennzoil and Quaker State Motor Oil!) Pithole seemed to epitomize a pattern of exploitation set by the gold rush and duplicated each time a new natural resource was discovered. The city was conceived in May 1865; by December it was incorporated. Fifteen thousand people had collected there virtually overnight. At its peak, Pithole had over fifty hotels, three churches, a theater, the railroad, and a red light district that the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette described as “the likes of Dodge City’s.” Following a financial panic, speculators began leaving town. A fire consumed 27 oil wells. By December 1866, the population of Pithole had dropped to 2,000. The 1870 Census recorded the population as only 237. Today, the site is a meadow of grass, remembered only by a small museum whose mailing address is, ironically, Pleasantville, PA.

How quickly this town came into being, and how quickly it became a ghost town! Photo courtesy Desert Rambler

Pithole came to mind this week when the EPA announced its “Affordable Clean Energy” rule. (Don’t you love how these names obfuscate their true nature?) The ACE plan will allow states to address greenhouse gas emissions from existing power plants, giving them leeway to set very modest goals, or even opt out entirely. Sixty-eight percent of America’s electricity is generated by burning fossil fuels.

In 2017, downwind states like Delaware and Connecticut put pressure on Pennsylvania's coal-fired power plants to curb emissions. Pictured is the Bruce Mansfield Power Plant in Shippingport, Pennsylvania. Read more in the Pittsburgh Gazette.

According to Ken Kimmell, President of the Union of Concerned Scientists, the EPA proposal is based on “blatantly crooked math” that overlooks the significant health and economic benefits of cutting carbon pollution, soot and smog. (Full disclosure: I have been a proud supporter of UCS since politicians started looking as science as opinion instead of fact.) “The administration is clearly intent on swinging its wrecking ball at two of the most important national policies that address climate change. Coming on the heels of the proposed rollback of EPA’s clean car standards, this shows the administration plans to sit on its hands while communities reel from heat waves, drought, wildfires and flooding, all of which are worsened by climate change.”

What will happen in Oregon? Our state’s last coal-burning power plant is operated by Portland General Electric Company. The Boardman facility was slated to stay online through 2040 but it will shut down by 2020 because of operating costs and environmental concerns. The industry is transitioning away from coal. That’s just reality, whether or not that truth is recognized by Trump’s base. But broader efforts to curb pollution in Oregon may depend on who controls the Governor’s Mansion. Kate Brown hopes to bring us into a cap-and-invest exchange that stretches from California into Canada. Republican candidate Knute Buehler redirects the discussion to forest health.

Why worry about fossil fuel emissions when our forests are burning? Oh, my. The political spin makes my head hurt.

As I write, Portland’s air quality sits at an unhealthy 168. Wildfire smoke gives us a sense of what air pollution looks and feels like as communities experience it throughout the U.S. Back in Simeon’s home state of Pennsylvania, there are still 78 coal-fired generating units.

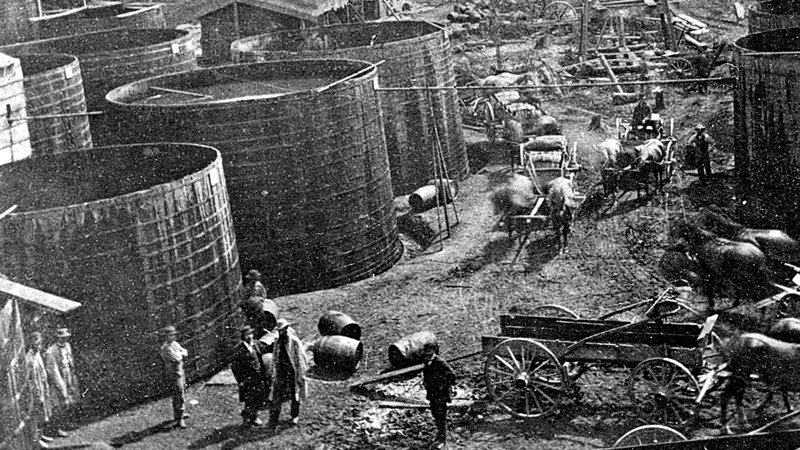

Holding tanks in Pithole, just before Samuel Van Syckel built the first oil pipeline linking the Frazier well to the railroad station five miles away. Photo courtesy Drake Well Museum. More info at American Oil & Gas Historical Society.

The speculators in Pithole could be denounced for their greed and for scarring the landscape. But they didn’t understand the long-term implications of burning fossil fuels. For them, it was an inexpensive upgrade from whale oil that could turn risk-takers into men of wealth. But we know better. Let us hope that we can get back on track before Pithole becomes an epithet for all of America.

Vagaries of History

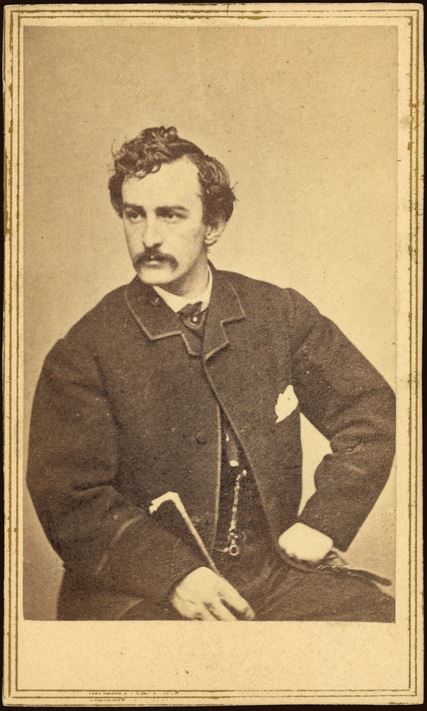

John Wilkes Booth: Oil Man

In late 1863, popular actor John Wilkes Booth persuaded two friends to join him in a new investment. They formed the “Dramatic Oil Company.” In January 1864, he made his first trip to Franklin, Pennsylvania and purchased a lease on the Fuller farm. In May, he drew his last paycheck as an actor, convinced he would make his fortune in oil. His company’s well produced 25 barrels of oil daily, but costs were mounting. Booth and his partners decided that “shooting” the well would increase production. Black powder was detonated deep into the well, but the strategy backfired and the well collapsed. Booth left the region in July, bitter and broke. Weeks later, he checked into a Baltimore hotel and began scheming against President Lincoln with boyhood friends. Over the next eight months, the plan evolved from kidnapping to assassination, culminating in Lincoln’s murder at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865. Twelve days later, he was shot to death by the Union cavalry. Two months after his death, oil was discovered at Pithole Creek about twenty miles from Franklin. The Homestead Well at Pithole Creek would yield 500 barrels a day.